|

| Brian Armour Jr. performs to music that he wrote the lyrics to at Studio Route 29 in Frenchtown, N.J. Photos by Wiley Henry |

|

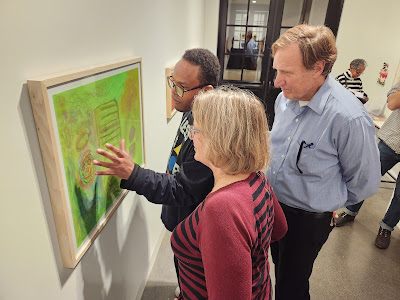

| Armour explains his artwork to a couple that admires one of his pieces on exhibit at the ArtYard. |

MEMPHIS, TN – Former Memphian Brian Armour Jr. danced for more than 20 minutes at Studio Route 29 in Frenchtown, N.J. He whirled in a black cape, and his moves – smooth, fluid, robotic, theatrical, mimetic – drew applauses.

The music was refreshing and original, courtesy of Hop Peternell, an artist and the studio’s co-director. Armour lip-synched the lyrics to three pre-recorded songs that he wrote with audio assistance from Peternell.

Studio Route 29, a 501c3 non-profit organization, is a progressive art studio for artists with developmental and intellectual disabilities. Kathleen Henderson is the executive director and an artist herself.

“Being in the studio with other artists, making surprising things, is just a joy every day,” Henderson said. “You never know what’s going to happen.”

Armour’s performance, however, was the prelude to an art exhibit that followed.

Known as B.J., Armour led his admirers down a short, tree-lined path to the ArtYard, where he and Ricky Bearghost, a textile artist from Portland, OR., have works on exhibit until Jan. 21, 2024.

The ArtYard is an incubator for creative expression and a catalyst for collaborations that reveal the transformational power of art. Jill Kearney is the founder and executive director.

The two-man exhibit, “You Come to Life,” opened Oct. 28. Bearghost, however, wasn’t available for the opening, but Armour carried on nonetheless, mixing and mingling.

When observers asked Armour to explain his artwork, he processed the request and explained the curlicues, organic forms, splashes of color, and the subtle nuances in his artwork.

“I like the artwork,” said Armour, speaking candidly about his simplistic drawings and paintings from dreams. “Everything is precise; everything is locked in. It’s not out of order. Everything is solid.”

Armour said he learned from the best. He credits his late mother and craft artist Deborah Towns Armour with passing on her artistic genes to him. He even assisted her in the studio and at art fairs.

“When my mom was alive, she couldn’t finish the art thing and the singing thing,” said Armour, honoring her memories in his own way. “I don’t know if it’s my soul that connects to her or not.”

It’s conceivable. However, they were inseparable – even when the vicissitudes of Armour’s life tried to rock his world and thwart his burgeoning talent for making art and music.

“Well, son, I’ll tell you: Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair,” the late Harlem Renaissance poet and playwright Langston Hughes began his popular poem “Mother to Son.”

For Armour and his mother, it wasn’t a crystal stair either. But they sufficed, to say the least – for she’d prepared him for a life without her.

Memphis was home to Armour since he was around six years old. Born in Germany, the doctors were unsure if he’d survive. That was 39 years ago. The malady he suffered at birth – including being born a preemie – was daunting and life-altering.

After his mother’s death last year, in January, Armour’s maternal aunt, Beverly Towns Williams, and her partner, Lionel Scriven, stepped in to fill the void. So, he went to live with them in Lambertville, N.J.

“I fell in love with him,” said Scriven, an architect.

Meanwhile, Armour is undergoing a rebirth, and Williams is amazed. But she was unaware that her nephew was drawn to music, moved by the dance, and immersed in drawing and painting.

Once Armour was settled in the home, Williams competed for services that the state of New Jersey offers for adults with special needs. “There are limited amounts of resources and a limited number of programs,” she discovered.

Williams wanted a comprehensive program that would teach her nephew independent life skills and skills to enhance his potentials.

“I was looking for a program that would be compatible with the things that he says he wants to do in life,” said Williams, an attorney.

She found it through the state’s Department of Human Services Division of Developmental Disabilities. It’s called the StarThrower Group, a nonprofit organization that renders services to adults like Armour with special needs.

“Because he expressed an interest in the arts, he was able to get an internship with Studio Route 29,” Williams said. “From there, he has just blasted off.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first installment of a two-part series about adults with special needs.

Copyright 2023 TNTRIBUNE. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment