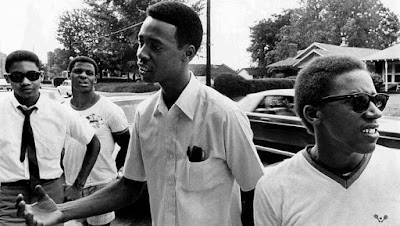

Whittier Alexander Sengstacke Jr.

During the turbulent 1960s, Whittier Alexander Sengstacke Jr. wrote cutting-edge news stories for the Memphis Tri-State Defender. If the surname sounds familiar, it’s because the name speaks volumes.

Sengstacke was the eldest son of the late venerable newspaper publisher Whittier Sengstacke Sr., and the nephew of the late publishing magnate John H. Sengstacke, who founded the Defender in 1951.

Sengstacke had been ill for a while and died the morning of Feb. 20 at Midtown Center for Health and Rehabilitation. He was 76.

In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, the respected journalist held the title of editor-in-chief at the Defender. He reported from the trenches and cobbled together breaking news stories from a Black perspective, which the mainstream press had largely ignored.

He was an eyewitness in the struggle for freedom and justice. For Black journalists during that era, fear no doubt was a constant reminder of the dangers that confronted them while they were trying to shed light on the age-old problem of systemic racism. Whatever confronted Sengstacke, he kept reporting the news.

His career highlights included covering hard news – police brutality, crime, politics – and other noteworthy news stories. He continued to write and performed other duties as well for the Defender into the late 1990s.

“He was a great guy, very knowledgeable of the newspaper business and didn’t mind sharing his knowledge,” said Marzie G. Thomas, publisher and editor of the Defender in the early 2000s.

“He had been in the business all of his life,” she said. “We loved Whit. He was a wonderful person. He always was so supportive of me.”

He also was supportive of Thomas’ predecessor, Audrey Parker McGhee, the Defender’s publisher and editor from the late 1980s until she retired in the early 2000s.

“He was well-grounded as a member of the Black Press,” she said, “not only because his father was head of the Defender, but because of the Sengstacke name. He always talked about his heritage.”

He was very courageous too, McGhee added.

Born in Chicago, Ill., Sengstacke received dual degrees in speech and journalism from Tennessee State University and applied his skills to the family business of newspaper publishing.

He was just as steeped in writing plays and performing on the stage as he was in journalism. He first thrived in his native Chicago before bringing his skillset to Memphis, where he settled down as a journalist for the Defender.

Ethel Sengstacke, a former TV camera operator, took note of her big brother’s work ethics and varied accomplishments in journalism, including his work in the theatre when she was much younger.

“He was always into theatrics,” she said. “He used to have a puppet show at the public library. We put on shows for the neighborhood kids. One time he built a stage and I fell off it.”

The injury still reminds Ethel Sengstacke of that harrowing experience. Other experiences were typical between a brother and his younger sister. “He was a big brother who always took me to the movies,” she said, “and he would give me advice.”

Pat Mitchell Worley remembers her uncle’s creative side. “He used to do art projects with me,” she said, “like papier-mâché, acting projects, and storytelling. He was the first to push the idea of storytelling.”

A memorial service for Whittier Alexander Sengstacke Jr. will be held in March. A date has not been determined. Serenity Funeral Home at 1638 Sycamore View Rd. in Memphis has charge.